Quimbaya (english version)

En otros idiomasTabla de contenido

-

1.1 Quimbaya: People and Gold in the Middle Cauca

-

2.2 Quimbaya at the Exhibition in the Gold Museum

-

2.1.3 Early Quimbaya Period

-

2.2.4 Late Quimbaya Period

-

2.1.3 Early Quimbaya Period

-

3.5 Quimbaya: Helmets, Nose Rings, and Poporos Symbols of Power of the Early Period

-

4.6 Lizard Men and Feline Lords: The Power of Transformation in the Middle Cauca in the Late Period

-

5.7 See also

-

6.8 Bibliography

-

7.9 Banrepcultural links

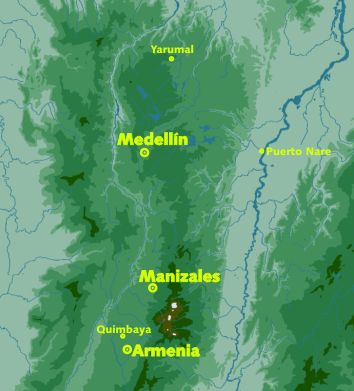

Quimbaya: People and Gold in the Middle Cauca

Poporo (a container for lime). Tumbaga 0 - 600 AD Loma de Pajarito, between Angostura and Yarumal, Antioquia 23.5 x 11.4 cm. For two millennia before the Conquest, the Middle Cauca was populated by farmers, ceramists, goldsmiths, and gold and salt miners. The goldsmithing of the Early Period (500 BC to 600 AD) shows iconic figures of leaders, men, and women as symbols of identity. The colors, brightness, and shapes of pumpkins, ahuyamas, totumas, and women alluded to fertility. A poporo or lime container in the shape of a woman of high rank in ritual attitude stands out.

Profound changes took place in the Late Period (800 to 1600 AD), with greater cultural diversity and population increase. The natives painted their bodies, wore beaded ligatures on their extremities, and inserted ornaments into their noses and under the mouth. Goldsmithing, which used copper much, and ceramics became geometric and schematic. With their ornaments and paintings, the caciques looked like jaguar-men, frog-men, and lizard-men. By 1540, due to differences in customs and language, Europeans classified the indigenous people in "provinces": Caramanta, Anserma, Arma, Picara, Carrapa, Quimbaya, Quindo, and others. Most were annihilated in the conquest.

Quimbaya at the Exhibition in the Gold Museum

For millennia, human groups with different cultures and ways of life took advantage of the diversity of climates and the variety and abundance of resources of the mountains of the Middle Cauca. Its first settlers, ten thousand years ago, were hunters and gatherers. Later, for about two millennia until the Conquest, in the Early Quimbaya and Late Quimbaya periods, farmers, pottery makers, goldsmiths, and gold and salt miners inhabited the region.

Early Quimbaya Period

Between 500 BC and 600 AD, the first goldsmiths were engaged in agriculture, hunting, fishing and gathering of wild fruits. They located their homes scattered on natural plains or on esplanades built on the slopes. They extracted gold from the sands of rivers and salt from sources of aguasal and used them to barter. The goldsmiths were specialists who made objects that were notable for their technical and aesthetic mastery. On them, they reflected aspects of the social organization and symbolic thought of their communities.

Both goldsmith and ceramic objects of this period have features such as smooth and shiny surfaces, sobriety in style, and realistic sculptural forms inspired by fruits and female figures. Human representations in goldsmithing show features such as nudity, rounded contours, thick torsos, triangular faces, protruding cheekbones, semi-closed slanted eyes, use of ornaments and ligatures, and hanging plates. These figures were symbols of the cultural identity of these groups.

The ornaments and ritual objects used by the leaders conveyed messages about their position, social ranks, and thought. In the middle course of Cauca and in the mountains of Antioquia, the costumes worn by these characters comprised few objects, almost all of them small in size. Nose rings and earrings made by the lost wax melting method in alloys of gold and copper or tumbaga were frequent. The notorious wear of many of the ornaments evidences their frequent use. Only helmets and crowns were large and visible emblems.

The poporos used to store the lime used with coca leaves were symbols of fertility for their colors and brightness as well as for their shapes of women, pumpkins, ahuyamas, and totumas. The leaders employed them in ceremonies aimed at the reproduction of nature and the well-being of society, where they themselves were seen as indispensable for the continuation of life. Also, some urns for the ashes of the dead that have been found buried in simple well tombs represented pumpkins and pregnant women, as if they were uteruses in which life is reborn after death. An ash urn in the shape of a paujil.

Another of the most outstanding objects in the collection at the Gold Museum is a poporo depicting a high-ranking woman adorned with facial paint, a helmet, and a nose ring. Her meditative expression and solemn posture holding bars with birds make her appear to be participating in a ritual. This master object, the two helmets, the crown with an imitation of feathers and two containers in the shape of an elongated totuma with a lid, probably used to store and carry the coca leaves, were part of the tools with which several leaders were buried in a tomb in the municipality of Puerto Nare, in the Middle Magdalena in Antioquia.

Goldsmiths of the early Quimbaya period also produced realistic and stylized figures of various animals. The most represented beings were snails and insects in metamorphosis, such as butterfly pupae, which may have had meanings related to the cycles of nature and society.

A pendant in the shape of a quadruped with a bird's head from Antioquia contained coal that was dated by the Gold Museum as far as 240 BC. Another zoomorphic pendant with two stylized animals has been dated from 190 AD.

Late Quimbaya Period

Since 800 AD, profound changes took place in the societies of the Middle Cauca. The population grew, as did also the production of agriculture, textiles, ceramics, and gold ornaments. Beliefs, objects, and symbols were transformed; primary burials in chamber pit tombs became common.

Body modifications and certain postures communicated characteristics of people, such as their social group and rank. In human figures buried with the dead to accompany and protect them, ceramists reproduced the body paint applied with seals and ceramic rollers, the ligatures of white beads that deformed arms and legs, and skull deformations. During the Late Quimbaya Period, goldsmith ornaments often had simple geometric shapes and schematic decorations. Some, such as ring-shaped and twisted wire nose rings, were commonly used. Ornaments were inserted into the fins of the nose, under the mouth, and on other parts of the face.

Societies of the Late Quimbaya Period inhabited the temperate zones with preference, both in scattered houses and in villages. They lived from agriculture, hunting, fishing, and gathering. They planted corn, beans, and sweet potatoes on the slopes, building threshing floors and ditches to control avalanches and erosion. They extracted gold and salt, spun, weaved, and worked on clay and metals, part of whose production they devoted to bartering with neighboring and distant groups.

Numerous objects were preserved which allow us today to have an idea of the daily life of these communities. For hunting and for war, they used spear throwers and darts made of palm wood. They hunted deer (Mazama), dantas (Tapirus), pecaries (Tayassu pecari), opossums (Didelphis), armadillos (Dasypus), rabbits (Sylvilagus), and other animals.

Spindle wheels made of ceramic were used in cotton spinning. The wheel, adjusted to the bottom of a wooden rod, maintained the rotational movement necessary to twist the thread and wind it around the spindle. These spinning instruments are so frequent that we can imagine that textiles were so too. A ribbon woven in cotton with hanging metal plates is preserved at the Museum and was dated 850 AD. Ceramic production varied within the Middle Cauca region. In the south, they made objects of multiple shapes, some decorated with black paint on a background of red, cream, or a combination of both colors. Also, the groups that had settled in the north of the Middle Cauca made a brown or gray pottery with rhomboidal shapes decorated with incisions and applied figures as well as orange vases adorned with white paint.

The production of copper objects was an important activity. With this metal, goldsmiths manufactured pectorals, bracelets, necklaces, and rattles.

By 1540, Europeans found a large and diverse population in the region of Middle Cauca, who suffered chaos and annihilation with the wars for conquest. The Spanish conquerors told in the chronicles that the caciques of this region lived in large houses surrounded by palisades where they kept images and the desiccated bodies of their enemies and performed cannibalistic rituals. They also related that they adorned themselves and dressed to look like animals; that they used metal ornaments and feathers, painted their faces and bodies, carried a long loincloth as a tail, their nails long as claws, and animal skins on their backs. Faced with differences in customs, language, and politics, Europeans classified the indigenous people into "provinces," which they called Caramanta, Zopía, Quincha, Irra, Anserma, Chanco, Arma, Paucura, Pozo, Picara, Carrapa, Quimbaya, Quindo, and others. Several of these names have survived in the geography of the region.

The goldsmith pectorals exhibit embossed figures of the jaguar-man, the frog-man, and the lizard-man, who probably represented the caciques in their ritual animal attires.

Quimbaya: Helmets, Nose Rings, and Poporos Symbols of Power of the Early Period

The objects made by the goldsmiths of the societies of the Early Period of the Middle Cauca and Antioquia served as symbols of prestige and power for their political leaders.

Goldsmithing included body ornaments, artifacts for the consumption of coca leaves, and musical instruments. The traces of wear, visible on nose rings, chopsticks, and other objects, suggest that they were used by these dignitaries in life. Upon their death, they were buried with them in large trousseaus such as the “Treasure of the Quimbayas,” the “New Quimbaya Treasure,” and several more, about which there is some documentation despite not having been found in scientific excavations. According to the few known archaeological contexts, it seems that the lower-ranking people used only a few nose rings and earrings.

By analyzing of the objects that make up the aforementioned trousseau and the human figures represented in them, it may be inferred that the outfits of the leaders included a helmet or a crown, one or several pairs of earrings, a nose ring, and a necklace with several turns. These ornaments did not form garments that covered much of the body.

Rather, they were restricted to the head and neck area and, except for helmets and crowns, were small and discreet. Helmets, used in other societies around the world for protective purposes in war, were employed here as emblems of prestige and as a source of spiritual power.

The tools used to consume coca included poporos (containers to store lime), collars for the poporos, sticks to extract lime, and pots to store coca leaves. These artifacts are distinguished by their large size (some poporos reach 35 cm high and some chopsticks measure more than 50 cm long), and by their rich iconography (several containers are realistic sculptures of human figures represented with great detail).

The entirety of this goldsmithing reveals a marked coherence in the style, which stands out due to the sobriety of its design and decoration, realistic shapes with rounded volumes, the brightness and smoothness of the surfaces, and the reddish colors for the objects. The forms reproduce the human figure with preeminence of the feminine, the fruits of pumpkins, calabazos and totumos, and animals such as snails and butterfly pupae. Various ornaments show geometric shapes based on curved lines. In the decoration, the openwork and the hanging plates that sometimes hide the figures predominate.

According to the analysis of the composition of a significant group of objects, apparently this goldsmithing was made entirely in tumbaga, the alloy of gold and copper, from where it acquires its characteristic reddish color. The metallic contents oscillate around 60% gold, 30% copper, and 10% silver. The latter is present because it is naturally associated with gold in the deposits. The small ornaments and the large containers as well were elaborated by the technique known as lost wax casting with core, in which goldsmiths were great masters. The helmets and crowns were made by hammering and embossing, also with great technical mastery. Due to its aesthetic and technical quality, this goldsmithing is considered as a first-order archaeological heritage of the country since the nineteenth century.

Lizard Men and Feline Lords: The Power of Transformation in the Middle Cauca in the Late Period

Gold Chest Piece 900 AD - 1600 AD Montenegro, Quindío 17.5 cm. During the Late Period of the Middle Cauca, goldsmithing continued to be a source of prestige for the leaders. However, the transformations that gave way to a new era revealed changes in the functions, forms, and technology of the objects that fulfilled this purpose.

In the early period, the containers and chopsticks for the consumption of coca together with helmets and diadems were the most visible emblems of power. In later times, circular pectorals, triangular nose rings, and sublabial ornaments of various types fulfilled this function. The forms of women and fruits were displaced by male and man-animal figures, geometric and zoomorphic. These symbols reveal the emergence of new ideas related to the position of leaders.

The flat circular pectorals stand out among the new emblems of power for their large size and elaboration. A significant amount of metal and work was invested in them. Some reach diameters up to 30 centimeters and several carry complex embossed designs. An iconographic study of these designs showed that they correspond to four basic categories or patterns: 1. Drawings based on geometric shapes and schematic birds; 2. Figures of lizards and perhaps other reptiles; 3. Stylized male anthropomorphic images; and 4. Human figures with animal features.

A careful look at these designs allows us to notice that the last three patterns make up a continuum of transformations. Man-animal figures mix elements from the other two categories: The head, the ornaments of goldsmithing, the sexual organs and the nipples are human, while the body, the body position, the tail, and the thickened fingers belong to reptiles. From this combination of elements, these figures can be interpreted as representations of lizard-men. Some of them also show a pair of rounded ears at the top of the head that resemble those of a feline, as if alluding to mixtures of man with more than one animal.

Thanks to archeology and ethnology, we know that American indigenous societies have held since ancient times a belief in the ability of some individuals to transform into animals and thus appropriate their faculties. Particularly, it is the shamans who have this ability, and who are true specialists in it. The transformations into birds, jaguars, and bats constitute the most widespread transmutations. In this way, the shamans manage to fly, wander hiding in the jungle, see in the dark, eat their enemies up, and observe the world upside down. These faculties are a source of great prestige and authority.

Anthropo-zoomorphic representations in pectorals, coupled with the descriptions of 16th-century caciques, suggest that Late Period leaders had powers of transformation. The chronicles tell that the “Lords” and caciques of the region profusely painted their bodies and decorated them as “cats”, carried animal skins on their backs, wore long loincloths like tails, and long nails like claws. It is likely that these transmutations were the source of admiration and respect for the shamans among their community. Burials in Uterus-Urns A circular Vision of Life and Death

Ceramic Vessel. 0 - 600 d.C. Santafé de Antioquia, Antioquia 20.5 x 40 cm.

Ceramic Vessel Early Period (0 - 600 AD) 8.8 x 23.6 cm.

Incineration of the corpse and burial of the burned remains in urns were the most common funeral practices in the societies of the Early Period of the Middle Cauca and part of Antioquia between 500 BC and 600 AD. The diversity in the way in which they carried out these practices indicates the existence of elaborate social structures and a rich symbolic thought around death and elaborate social structures.

They almost always used ceramic vases as urns to store the ashes of the dead, although sometimes they also used small stone sarcophagi or metal containers. They were usually covered with bowls or other urns and were sporadically placed on a stand. Inside the urns they deposited the remains of one or several individuals, sometimes infants and adults, and other times also animals, apparently birds. These vessels were deposited in irregular and shallow pits between 50 and 150 cm deep, sometimes inside a niche that was dug in the ground. Sometimes the builders placed stone slabs over the top of the pit to keep the area surrounding the urn clear.

Most of the tombs of this period are located on the terraces for housing, inside the area of the houses or in their surroundings, or near the places of habitation. Less often they have been detected on hilltops and high places. Archaeologists excavated an exceptional site in southwestern Antioquia where urns had been buried under large rocks that surrounded the space used for housing. It was a place that was undoubtedly given special significance.

The urns are widely varied in terms of quality, shapes, and decorations. In many cases, they used containers for domestic use with simple forms and rustic finishing for this purpose, while in others they used vessels that were made expressly for this function. Among the latter, the most common have a cylindrical shape and a little bulging toward the base, often with reliefs or protuberances, that are reminiscent of the fruits of pumpkins (calabazos). Others show globular or animal forms, such as paujil-like birds, and some, the most elaborate, represent female figures with prominent bellies huddled together, suggesting women giving birth.

See also

The Lettuce Archaeological Heritage Muisca Zenú Calima

Bibliography

Materials in the Bibliographic Collection

Banrepcultural links

Quimbaya Gold Museum | Website of the Quimbaya Gold Museum External Links

⧼banrepcultural-no-categories⧽